TEMPLE GRANDIN’S CENTER TRACK RESTRAINER

AND CURVED CHUTE SYSTEM

AN OPEN LETER

By Liz Marshall

01.25.14

Robert, thanks for presenting your experience and analysis of the Grandin scene in the film. Overall, the film is not prescriptive, telling people what to think or feel. Instead, it is created to inspire self-reflection about a big and complex issue, and to reach a broad audience. When speaking with people about the film, some don’t understand the meaning or purpose of the Grandin scene, and they are upset that she is in it. Others appreciate the gravity of the scene, and the inclusion of her ideas for a variety of reasons. It has been suggested that I write an open letter explaining why I included Grandin in the film, to unpack the sequence for people, explaining its purpose and meaning. I have been pondering this, although I believe the film should speak for itself. When making a film like this, nothing is random, every moment, transition, word and image is deeply considered to support the thesis. The thesis of The Ghosts in Our Machine is that all animals are sentient.

– Liz Marshall / Facebook. December 7th, 2013.

(In response to a post by activist Robert Grillo, Free From Harm)

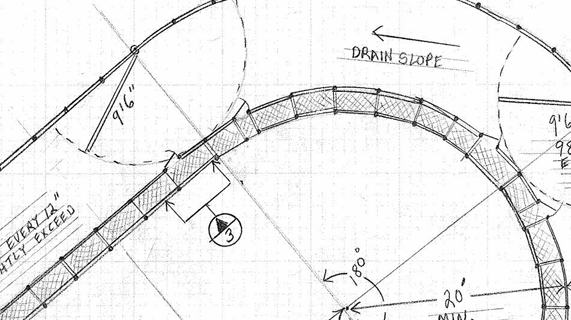

On a few occasions I’ve been asked about the following scene in THE GHOSTS IN OUR MACHINE documentary, a scene that has puzzled and roused feelings of concern for some activists. It features Temple Grandin’s Center Track Restrainer and Curved Chute System.

I believe a film speaks for itself without the need for explanation. That said, in light of my responsibility as a social-issue documentary filmmaker, I agree it’s a good idea to unpack the scene for you. I hope this helps.

About three quarters of the way through THE GHOSTS IN OUR MACHINE there is a sequence where cattle are led through a maze, and we see macro close ups of detailed hand-drafted designs of a carefully constructed labyrinth called the Center Track Restrainer and Curved Chute System. To accompany these images we hear the voice of its architect Dr. Temple Grandin, Professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University. Grandin describes the functionality of this system, and archival video footage is seen of many cows being led to slaughter, it concludes with the brief yet harrowing ritual slaughter (halal) of two of the cows. The stock footage is excerpted from Grandin’s educational DVDs entitled “Cattle Handling Principles to Reduce Stress” and “Cattle Handling in Meat Plants“.

This sequence is an intimate window into the rationale and efficiency of the world’s largest slaughter system, employed largely in parts of North America and in Australia. I could have sought out the goriest footage imaginable to prove the point that all slaughter, whether “humane” or not, is morally corrupt. Instead, I found it much more relevant and compelling to the film’s thesis to include the voice and work of a highly regarded innovator within today’s global meat industry. I chose to place Grandin’s ideas and designs within the context of the film’s thesis – at this juncture in the film the audience has been led on a point-view journey through the lens and heart of activist photographer Jo-Anne McArthur, and are attuned to the sensory conscious and feeling worlds of a colourful cast of nonhuman animals. The Grandin scene is a jolt away from this worldview, back to a normalized accepted way of seeing animals as production units. This abrupt shift in perspective is part of why the scene is shocking. As a note, for those who have witnessed brutal images of widespread primitive forms of slaughter through the internet or elsewhere, this footage is relatively sanitized, hence the title of the film The Ghosts In Our Machine.

To contextualize this scene, it’s important to mention what comes before and after ~

Before is a point-of-view sequence which follows Jo-Anne McArthur through the streets of New York. We see meat everywhere: on the grill; in shop windows, on billboards. By conveying the normalcy and scale of meat consumption juxtaposed by a committed hopeful vegan activist walking amidst a sea of people, this scene has David and Goliath allegorical overtures: the big guy and the little guy (it’s one of my favourite scenes). From there we transition to the interior of a sanitized meat packing plant where we see slabs of animal parts hanging from hooks, being cut into pieces by workers, and then to Grandin’s Center Track Restrainer and Curved Chute System.

Immediately following the Grandin sequence there is release. The film cuts back to Farm Sanctuary in upstate New York where rescued elderly cows walk peacefully up a hill, an old wise goat with a long beard chews his cud, and Jo walks up an adjacent gravel road with a spring in her step carrying her farm boots. We know she has returned to her heavenly refuge for a visit with animal friends, and with her pal Susie Coston, the National Shelter Director for Farm Sanctuary. This is the third and final scene at Farm Sanctuary, where the scenes are crafted as magical (yet very real) departures; transporting audiences to ancient deep memories of childhood and storybooks where all animals are friends with names and stories.

It was early January 2012, when I found myself en route to Colorado with Cinematographer John Price and Sound Recordist Jason Milligan, to spend the day with Temple Grandin, to interview her about her Center Track Restrainer and Curved Chute System. It was preplanned that she would describe the details of her drawings for me. By the end of the day, after an interview in our hotel she invited us back to her home to show us her plaques and awards from McDonald’s and other clients. Her home was dusty and cluttered with books and images of animals; especially cows and western cowboy iconography, and there were paintings of animals, statues of animals, and books about animals everywhere. Her parting words to me were that she hoped I had learned something from her, and I asked her what she would like me to have learned, and she explained that she is a pragmatist; most people in the world eat animals, and so she sees her work as helping to improve things.

I left with a stack of DVDs given to me with the rights to use the footage and an interview in the can. While traveling home I wondered how I would make sense of it all. It wasn’t until the summer (5 months later) that Editor Roland Shlimme and I started to deeply consider the footage and its meaning and intent for the film (I had since viewed it a few times and had edited a rough interview sequence). In September 2012 I viewed Roland’s first edit, and remarkably it didn’t change much after that.

Documentary films and photographs inspire people to see the world differently.

THE GHOSTS IN OUR MACHINE contrasts an accepted way of seeing animals as food, with a new way of seeing animals as friends, which is why I feel the Grandin sequence is powerful and effective within the context of the film’s thesis.

For The Ghosts,

Liz Marshall

Director, Producer, Writer

Toronto

Thank you for this wonderful and emotional movie about the non human animals with whom we share this earth. After watching a screening of this movie in Montreal, I was struck by how reflective the audience(vegan and non vegan alike) seemed to be. I think that if we as vegans can help people to tap into this reflective sides of themselves, much of the work non human rights activists do for these beings will be done.

I ask myself daily what can one vegan, like myself, do to make a change when the need is so urgent?

I think that information, education and inclusion is important-talking about the ethics of veganism rather than moralising about it. But it is tough. I would like to tell people to just stop-just Stop!! But I am pretty sure that does not work.

I will keep telling people about this wonderful film, encouraging them to see it, all the while hoping and wishing for the end to the suffering.